Sam Himelstein, PhD

Sam Himelstein is the founder and CEO of the Center for Adolescent Studies, Inc. He is passionate about working with youth and training the professionals that serve them.

Trauma and the Brain: An Introduction for professionals working with teens

Trauma can be defined as a deeply distressing response to a real or perceived threat to one’s life. Trauma can result from events including, but not limited to, getting physically or sexually assaulted, sudden death of family members or close friends, being emotionally abused or neglected throughout one’s childhood, the result of a catastrophic environmental event like an earthquake or hurricane, and can even result from generations of oppression on a family or community. Trauma is traditionally popularized as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a severe adaptation to threat characterized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as having re-experiencing symptoms (e.g., flashbacks, nightmares, daydreams of the traumatic event), avoidance symptoms (e.g., avoiding the physical place where the event occurred, avoiding/suppressing thoughts related to the event, etc.), and arousal symptoms (e.g., hyper or hypo-vigilance; i.e., rapid increase/decrease of the individual’s physical “alarm” system such as heart rate and other autonomic nervous system functions). This definition however, can be limited and does not take into account the many nuances of subjective experience and behavioral expression. For example, a young child who’s mother neglected him and in turn developed an insecure ambivalent attachment style may develop a worldview that’s very cold and harsh relationally; a young woman living in a community plagued by violence and drugs, but who’s never been assaulted physically herself can still develop hyperarousal in response to constantly hearing gunshots. These are just a couple scenarios in which trauma can occur and fall outside the exact criteria of PTSD.

Most educators, therapists, and other youth workers know inherently that every young person doesn’t fit in a predefined diagnostic box. We know our students and clients have varied experiences that have impacted their lives in many ways, which can manifest in our classrooms and therapy offices diversely. What’s often missing is a basic understanding of how trauma impacts the brain and how such function, in turn, affects behavior. Knowledge of the traumatized brain can drastically improve how we engage our young people in order to practice a trauma-informed approach.

An Introduction to Trauma and the Brain

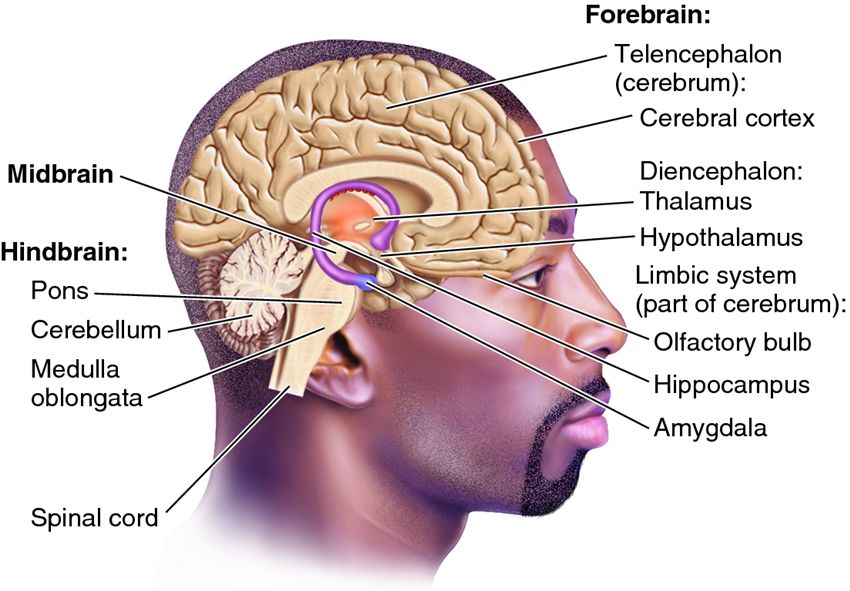

First, a quick primer on the brain. There is the hindbrain or reptilian brain, which includes the brainstem and cerebellum. This controls all the essential functions we don’t need to think about such as breathing, using the bathroom when we’re infants, etc. Next is the mid-brain. This includes the limbic system and often gets pegged as the “emotional” brain. Finally is the forebrain, which includes the neocortex and is responsible for our higher order functions like language, abstract reasoning and of course executive function. The major structures of the brain involved in processing trauma are the thalamus, the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the hippocampus.

Thalamus

The thalamus sits atop of the brain stem and is responsible for processing external stimuli. Sounds, images, any of the senses are first sent through the Thalamus, or as I like to call it the “gatekeeper.” The thalamus is like a gatekeeper or bouncer at a club. They are the first to receive all the action; everything that wants to “get in.”

Amygdala

The amygdalae are two almond shaped parts of the brain in the limbic system that picks up where the thalamus left of. Whereas the thalamus processes initial sensory information, the amygdala interprets it. Bessel Van der Kolk calls the amygdala the “smoke detector” because it can be akin to a smoke detector sensing smoke or fire. This “alarm” system alerts us (swiftly and unconsciously) of whether an external stimulus is a threat.

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is also part of the limbic system and is associated with memory. When the amygdala is triggered into an alarm state (i.e., a threat is perceived and the smoke detector goes off) it also relies on past memory/experience (e.g., a past threatening experience that is again happening currently).

Hypothalamus

When the amygdala and hippocampus work in tandem to declare threat, the hypothalamus quickly sends a message down the brain stem. This activates autonomic nervous system functions like increased or decreased heart palpitations, sweating, etc. and sends the body into fight, flight, or freeze states.

Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex is mentioned here only because in normal processing, if the amygdala perceives no threat it quickly establishes connection via the anterior cingulate with the prefrontal cortex. This enables language, abstract thought, executive function, etc. However, when the smoke alarm is triggered and a message is sent via the hypothalamus to the hindbrain, all connection with the prefrontal cortex ceases. That means all normal executive functions and normal modes of thinking/perspective-taking are offline. Overtime, this of course leads to a number of issues for individuals including decreased self-regulatory abilities and a constant state hyper or hypo-vigilance (depending on the individuals adaptation of the trauma) with a decreased ability to manage such states. A common example referenced in the literature is a person encountering a snake in the woods and being startled (sensory information taken in by the thalamus), and threatened (via the amygdala). In the future, they may be walking around the corner of their home and become just as startled, and perceive just as much threat by seeing a coiled up hose and mistake it for a snake (that’s the hippocampus working in tandem with the amygdala).

With the youth we work with, this shows up in many ways. One of the most common situations I hear of involve youth who mistakenly perceive another person’s facial expression as a threat when it may not be. I once had a young man tell me:

“Sometimes when I see a person across the street, it makes me clutch my gun because you never know what they’re about to do. But now when I think about it’s like, ‘what if that’s someone that knows me and my family and just recognizes me from family pictures.’ I’m about to shoot someone for no reason and who wasn’t even trying to rob me or hurt me.”

This type of trauma adaptation also happens in interactions between students and teachers, with teachers unintentionally triggering students’ trauma. Sometimes a youth will be not that engaged in class, or sometimes will be very disruptive (the manifestation of the trauma behaviorally). In turn, teacher will try to manage the classroom by telling the youth to be quiet. It oftentimes comes across negatively with a harsh tone and in front of the rest of the class. They give multiple directives and wonder why the youth isn’t complying. One time a youth told me a teacher simply “talking at” him in class set him off. He couldn’t even listen to the actual words coming out of the teacher’s mouth. All he was aware of was the anger consuming him. His amygdala (in tandem with the hippocampus) was setting of his alarm system given that he’d been emotionally and physically abused as a child. His trauma manifests behaviorally by an aggressive outburst, cusses out the teacher, and storms out of the classroom. The youth then gets labeled as a “trouble-maker” when in fact his trauma was triggered by an unskillful approach to classroom management.

Trauma manifests in many ways in the classroom, therapy room, and other youth work settings. What’s most important is that professionals have an understanding of how trauma affects the brain and how sometimes youths’ behaviors really are a result of triggered trauma and not simply a “decision” to defy you as the adult. With deeper understanding and integration with present-moment practice, teachers, therapists, and other youth workers can be compassionate and use their understanding as a mechanism to build relationships, safety, and trust with the traumatized youth. The key is for us adults to not function from a place of ego, needing to be right, or authoritative assertion, but rather a compassionate, understanding, and relationship-based perspective. Such a relating style illustrates a trauma-informed approach.

For ongoing training on trauma-informed care and building authentic connections with those you work with, join our monthly professional development calls! Learn more about our FREE Training Community and join us now!

Related Posts

2 Tips for Working with Resistance and Traumatic Adaptations

3 Ways Compassion Can Help Youth Impacted by Trauma

3 Ways Movement Can Help Trauma-Impacted Youth

10 Essential Guidelines for Teaching Meditation to Trauma-Impacted Youth